The five finger approach to sleep-wake complaints

Dr. David E. McCarty discusses the complex issues of sleep apnea and how the five fingered approach can help patients to participate in their own problem solving.

Dr. David E. McCarty offers a collaborative patient-centered problem-solving tool for a complex world

The complexity of sleep apnea

Because it arises from multiple overlapping anatomic, physiologic, and functional deviations from optimum, with variable representation of obstructive versus central apnea processes, the entity known as “Sleep Apnea” is best characterized as a complex phenomenon1 for which there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution.2 What’s more, clinical management of breathing- and airway-related pathology requires navigation of countless non-apnea contributors to sleep-wake complaints, nesting the complexity of the breathing/airway issues within the complexity of a larger spectrum of sleep-provocative disease.

“Complex” environments differ from “complicated” ones by virtue of their unpredictability. For example, the cockpit of a 747 can be considered a “complicated” environment. Sure, there are scads of dials and knobs, but with the right training, you’d know just what to do to get a predicable result from that machine: you’d take off, you’d fly, and you’d land, and it would be predictable.

On the other hand, a “complex” environment involves variables that may be hidden to the problem-solvers, responses to therapy being less predictable. Compared to an aircraft cockpit, a “complex” environment is more like a Brazilian rainforest.3

Complicated environments tend to run efficiently with expert, top-down management styles. On the other hand, complex environments require a different mindset, one which is receptive to new information and intentionally collaborative.3

To explore this, let’s go to war…

Gen. Stanley McChrystal, Al Qaida in Iraq, and the Team of Teams

In his bestselling book Team of Teams, Stanley McChrystal (U.S. Army Gen, retired) describes his real-world approach to complexity and his successful strategy to harness true collaboration among America’s most elite strike forces: Navy SEALS, Army Rangers, Army Delta Force, and Air Force Special Tactics.4

Under McChrystal’s command, this consortium faced a devious and dangerous enemy called Al Qaida in Iraq in the early 2000s. In short, he found that these elite forces had difficulty merging their efforts at first — the squads seemed to compete with one another in the field and had trouble predicting one another’s contingencies. Instead of enhancing one another’s efforts, squads often squabbled and defended their internal honor.

He described the phenomenon as feeling like the coach of a soccer team of exclusively world-class players, all of whom happened to play the game with blinders on.

McChrystal understood that he wouldn’t be able to command his way out of his predicament. He realized he needed to create an environment where collaboration would arise naturally. To do this, he introspectively asked what would make a good soccer team.

His answer included two elements:

- Team-members needed to share an understanding of the playing field — what it looked like, what the rules were, and how things fit together — in other words, all players possessed a “shared consciousness” of the complexity of the situation.

- Team-members had to experience “lateral connectivity” — a term which for McChrystal basically boiled down to a combination of “trust” and “empathetic connection.” Trust empowers an upfield player to kick the ball to an empty spot downfield, born of an empathetic bond with her teammate — whom she knows is fast enough to get there, and carries the shared consciousness that that’s where she’s expected to be.

To enhance team-wide shared-consciousness, McChrystal created an open-command-post mission control center, with planning stages open to all key members of the mission: even translators, drivers, and non-military governmental agencies like the CIA and FBI. As a leader, he was present, active, and available. Very few details were deemed “need to know.”

To enhance lateral connectivity, McChrystal instituted a cross-team embedding program — a SEAL would embed with the Rangers, for example, or a Delta would fly with Special Tactics.

Ultimately, McChrystal’s “Team of Teams” would go on to eliminate their most dangerous target, the charismatic radicalized leader of Al Qaida in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a success McChrystal attributed to collaboration and field-empowered decision-making:

“At the core of the Task Force’s journey to adaptability lay a yin-and-yang symmetry of shared consciousness, achieved through strict, centralized forums for communication and extreme transparency, and empowered execution, which involved the decentralization of managerial authority.” 4

Complexity, collaboration, and Dave Snowden’s Cynefin Framework

Dave Snowden is a social scientist who specializes in making sense of complexity.5,6 He popularized the concept of collaborative decision-making in the business world and continues to consult for titans of industry.7 The following passage — taken from an essay Snowden wrote for Harvard Business Review in 2007 — observes breakthroughs when a leader is receptive to new information:

“Instructive patterns … emerge if the leader conducts experiments that are safe to fail. That is why, instead of attempting to impose a course of action, leaders must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself. They need to probe first, then sense, then respond.”3

What Snowden describes here is essentially responsive listening, echoing the foundational ethos of patient-centered medicine. When he advises leaders to conduct “experiments that are safe to fail,” clinicians recall the scientific basis for the old-fashioned “N of 1” clinical treatment trial.8 Substitute “examine-diagnose-treat” for “probe-sense-respond,” and the parallel to patient-centered medicine is clear.

Complexity requires collaboration

Arguably, skillful navigation of complexity is the “art” of clinical practice. McChrystal’s wartime experience and Snowden’s work on complexity sense-making both suggest a method behind the “art,” with a receptive and collaborative posture at its foundation. It follows that providers best able to collaborate with their patients will be most successful navigating through medically complex terrain. The challenge we face is to communicate the complexity of the landscape of sleep medicine to our patients in an understandable and practically useable way.

The Five Finger Approach

The “Five Finger Approach” is a patient-centered collaborative clinical tool which organizes the complexity of problem-solving sleep-wake complaints into five functional and actionable domains:

- circadian misalignment

- pharmacologic factors

- medical factors

- psychiatric/psychosocial factors

- primary sleep medicine diagnoses.9

When used as a collaborative bedside tool, this framework helps patients participate in their own problem-solving by promoting a shared consciousness for the complexity that’s being deconstructed. When each domain is collaboratively explored by provider and patient, the partnership can identify actionable sources of suffering, discomfort, and dissatisfaction with the sleep-wake experience that otherwise would remain unseen and unaddressed.10

To properly explore the first two domains (circadian misalignment and pharmacologic factors), we’ll need to review some basic concepts of circadian neurobiology and clinical epidemiology.

First, let’s look at circadian misalignment.

Exploring circadian misalignment

The competing drives for “sleep” and “wake” can be summarized using a framework that’s called the Two Process Model of sleep-wake regulation.11 The two processes governing “sleep” and “wake” are called Process S (the “S” stands for a concept known as “sleep pressure”) and Process C (the “C” stands for “circadian”).

When the circadian drive to promote wakefulness is misaligned with the desired timeframe for sleep, the sleep-wake experience becomes problematic. It’s common for evening environmental variables to contribute to a delay in circadian sleep phase — creating a type of “social jet lag” which manifests as sleep-onset insomnia and morning grogginess.

The complexity of these topics can be easily shared with patients, as will be explained below.

Process S: Fumes in the Attic

The concept of Process S can be easily explained by using the concept of “fumes in the attic.”12 The longer we’re awake, and the more active we are, the more “fumes” will build up in our “attic.” When “fumes” get too thick, we get sleepy, bleary-eyed, brain-fogged. When we fall asleep, fumes clear out — it’s as if we’ve opened up all the windows in the attic to allow a cross-breeze to ventilate all those fumes away!

The cartoon on the next page illustrates the concept with a bit of whimsy.

Process C: Circadian Maintenance of Alertness

The deep brain neuronal structures keeping us awake are collectively referred to as the “Ascending Reticular Activating System” — “ARAS” for short. Stimulating these neurons makes us feel more awake. Damaging or blocking these neurons makes us feel sleepy, due to unopposed activity from Process S.

The neurons of the ARAS are programmed to fire at different levels, depending on the time of day, a process regulated by the seat of our circadian rhythm, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).13

Toward the end of the day, during roughly the 3 hours before our usual prolonged nocturnal sleep interval, the ARAS fires at high levels. This makes sense, because by the end of the day, there’s a lot of sleep pressure (i.e.: Process S, i.e.: “fumes”) hanging around. At that point, the ARAS must work hard to counterbalance the fumes, so it dials way up.13

This is the “second wind” our patients might recognize, in the early evening.

Researchers of circadian sleep biology have termed this timeframe in the circadian cycle the “forbidden zone” because biologically, it’s difficult for one to sleep during this timeframe of robust ARAS activity.14 Delaying the “forbidden zone” contributes to “social jet lag” symptoms, like sleep-onset insomnia and morning grogginess.15

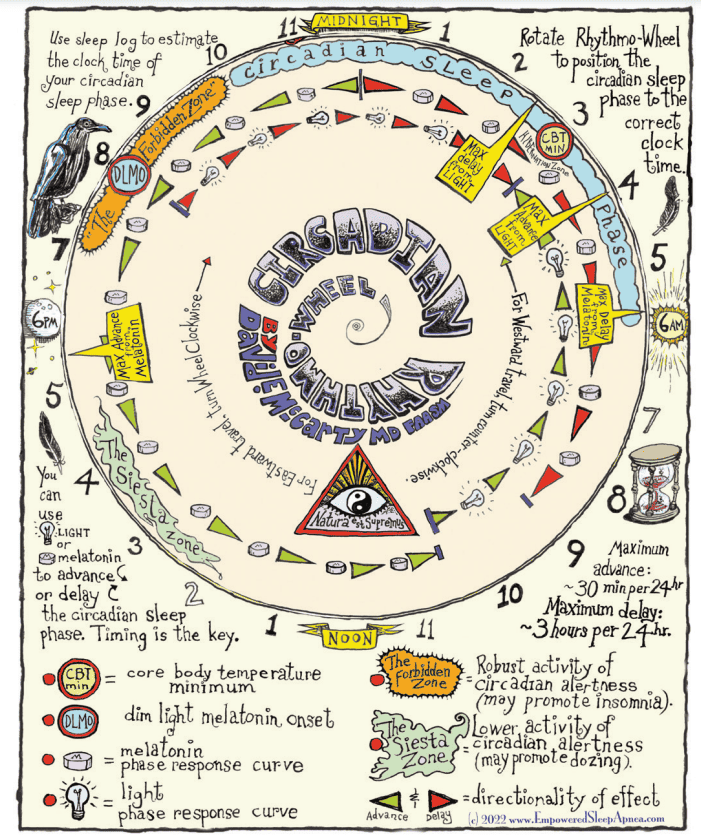

Teaching about circadian biology is enhanced with the use of visual aids, such as the interactive wheel shown in Figure 2.

Patients are often surprised to learn that common environmental variables in the timeframe of the “forbidden zone” — not just electric lights, but also social stimuli, such as eating, excitement, and exercise — all promote a subsequent delay in the sleep phase, thus compounding “social jet lag” misalignment symptoms.

Exploring pharmacologic factors

Prescription medications and social drugs (like nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, and, increasingly, marijuana) can have profound influences on sleep and wake. That’s why a diligent, non-judgmental pharmacologic review is essential in any investigation of an individual’s sleep-wake complaints.

How does one decide if a medication or drug is playing a role in a patient’s sleep-wake complaints? Evidence-based medicine pioneers, Sackett, et al., recommend a studied evaluation of whether there’s a repetitive signal in the published literature suggesting that the agent in question can cause the type of harm you’re worried about, coupled with a temporal sequence of exposure and outcome that makes sense for the narrative you’re dealing with.14

This bit of detective work is enhanced when patients understand the nature of the search and are deputized as active agents in the problem-solving process.10

A list of common pharmacologic factors affecting sleep-wake is listed in Table 1 on the following pages.

Exploring the last three domains

The last three domains of the Five Finger Approach are

- Medical Factors

- Psychosocial/Psychiatric Factors

- So-called “Primary Sleep Medicine diagnoses”

The final domain is the mental location to file our patient’s “known sleep diagnoses” and to question whether other common diagnostic labels might have been overlooked.

Strategically, these three domains are methodically addressed with the patient similarly to the first two, striving to engage Snowden’s mindful “probing” as a first step. In each setting, the process involves engaging the patient, probing collaboratively whether elements in that domain could be a factor contributing to their personal concerns, and then collaboratively exploring potential solutions.

What we’ve learned

- Sleep Apnea — and the practice of Sleep Medicine — is not complicated, it’s complex! There’s a difference!

- Complicated environments benefit from the efficiency of a top-down management style, run by an expert.

- Complex environments benefit from collaborative decision-making responsive to unpredictability. This requires an approach of intentional probing and receptivity to change plans as new information arises.

- Collaborative teamwork requires: 1. a shared consciousness of the system’s complexity and 2. lateral connectivity (i.e., trust and empathetic connection) between team-members.

- In a patient-centered clinical relationship, the patient is a member of the team.

- “Root cause” complexity for sleep-wake complaints can be deconstructed with a “five-finger” collaborative exploratory tool: 1. circadian misalignment, 2. pharmacologic factors, 3. medical factors, 4. psychosocial/psychiatric factors, and 5. primary sleep medicine diagnoses.

- Communicating and strategizing collaborative understanding of the first (circadian misalignment) and second (pharmacologic factors) domains requires a basic familiarity with simple concepts of sleep-wake/circadian biology and clinical epidemiology. These concepts are worthy of further study, as mastery improves the ability to characterize this complexity for our patients.

David E McCarty, MD, FAASM, is a Sleep Medicine clinician, author, cartoonist, and podcast creator/host. He is the co-author of Empowered Sleep Apnea: A Handbook for Patients and the People Who Care About Them, and the creator and co-host of Empowered Sleep Apnea: THE PODCAST.

David E McCarty, MD, FAASM, is a Sleep Medicine clinician, author, cartoonist, and podcast creator/host. He is the co-author of Empowered Sleep Apnea: A Handbook for Patients and the People Who Care About Them, and the creator and co-host of Empowered Sleep Apnea: THE PODCAST.

- McKeown P, O’Connor-Reina C, Plaza G. Breathing Re-Education and Phenotypes of Sleep Apnea: A Review. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 26;10(3):471.

- McCarty DE. There is No OSFA: How the Many Moving Parts of Sleep Apnea Demands Precision Medicine. Dental Sleep Practice. Spring 2023;10(1): 18-20.

- Snowden DJ, Boone ME. A leader’s framework for decision making. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harv Bus Rev. 2007 Nov;85(11):68-76, 149.

- McChrystal S, Collins T, Silverman D, Fussell C. 2015. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York: Portfolio/Penguin Books; 2015.

- French S. Cynefin, statistics and decision analysis.Journal of the Operational Research Society. 64:4, 547-561.

- Kurtz CF, Snowden DJ. The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM Systems Journal. 2003;42(3): 462-483.

- Cognitive Edge Ltd & Cognitive Edge Pte. The Cynefin Company and The Cynefin Centre, Conwyll, Singapore, Wilmington. https://thecynefin.co/. Accessed June 13, 2023.

- Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Tugwell P, Guyatt GH. N of 1 Trials: Selecting the Optimal Treatment with a Randomized Trial in an Individual Patient. In: Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine (2nd Ed). Boston: Little Brown & Co.;1991:223-238.

- McCarty DE. Beyond Ockham’s razor: redefining problem-solving in clinical sleep medicine using a “five-finger” approach. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010 Jun 15;6(3):292-296.

- McCarty DE. Sometimes, You’re the One. OR: The Story about How the Five Finger Approach Found a Problem That Had Never Been Described and How it Changed Wendy’s Life. In: Dave’s Notes the official blog of Empowered Sleep Apnea: Published online November 18, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://www.empoweredsleepapnea.com/daves-notes/sometimes-youre-the-one.

- Borbély AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. 2016 Apr;25(2):131-143.

- McCarty DE, Stothard E. Empowered Sleep Apnea: A Handbook for Patients and the People Who Care About Them. Pennsaukin Township, NJ: BookBaby Press;2022.

- Gabehart RJ, Van Dongen HPA. Circadian Rhythms in Sleepiness, Alertness, and Performance. IN: Kryger, Roth, Dement, eds. Principles & Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th Ed. Elsevier Press, 2017:388-395.

- Strogatz SH, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Circadian pacemaker interferes with sleep onset at specific times each day: role in insomnia. Am J Physiol. 1987 Jul;253(1 Pt 2):R172-178.

- Stothard ER, McHill AW, Depner CM, Birks BR, Moehlman TM, Ritchie HK, Guzzetti JR, Chinoy ED, LeBourgeois MK, Axelsson J, Wright KP Jr. Circadian Entrainment to the Natural Light-Dark Cycle across Seasons and the Weekend. Curr Biol. 2017 Feb 20;27(4):508-513.

- Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Deciding Whether Your Treatment Has Done Harm. IN: Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine (2nd Ed). Boston: Little Brown & Co.;1991: 283-304.

Pediatric dentists should be aware of both sleep apnea and airway issues in children. Read Dr. William Hang’s “Pediatric dentists are the obvious ones to help children breathe, sleep, and prosper!” at https://pediatricdentalpractice.com//pediatric-dentists-are-the-obvious-ones-to-help-children-breathe-sleep-and-prosperpost/